Introduction to Git and GitHub

Class 2: GitHub

Objectives

In the last class, we used the GitHub Desktop application to work with version control on our own computers by creating repositories, tracking changes using the basic Git workflow (modify-add-commit), exploring history, and ignoring files.

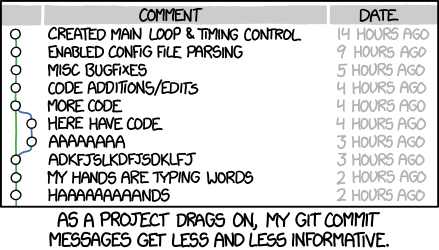

Now that you have some experience with version control using Git, you may be able to appreciate this cartoon from XKCD:

Today, we’ll transfer our knowledge to working with remote repositories on GitHub. By the end of this class, you should be able to:

- differentiate between local and remote repositories

- use GitHub to publish your own code/data

- contribute to someone else’s repository using GitHub

Introduction to GitHub

In our previous class, we focused on git for local repositories, which means applying version control for files and directories located on our own computers. In this class, we’ll expand our understanding of version control to include working with remote repositories vit GitHub.

GitHub is a web-based platform for sharing and collaborating with code and data. It allows you to create repositories that are publicly visible, or private but accessible to specific people to whom you provide permission.

You registered for a GitHub account and used that information when setting up the GitHub Desktop app in our previous class. If you log on to GitHub with your account information, you can access a number of features including:

- a profile, where you can include information about yourself

- starring repositories and following other people

- a timeline/newsfeed, which will include notifications about recent projects and activities for yourself and people you follow

In addition to individual accounts, groups of individuals working together can create GitHub organizations. There are two relevant GitHub organizations for us:

- fredhutch.io: holds repositories containing course materials, as well as the code for the fredhutch.io website. All of these are publicly available repositories.

- Fred Hutch: projects from Scientific Computing and other groups at Fred Hutch, as well as the code behind the Fred Hutch Biomedical Data Science Wiki. Many of these projects are public, although there are also some that are viewable only to members or specific teams.

As a Fred Hutch affiliate, you are welcome to join the Fred Hutch GitHub organization. To learn how, as well as other information about this feature, please see the Wiki GitHub page.

GitHub Teams are another way of organizing individual accounts and providing permission to private repositories. The Wiki, for example, includes a group of members from the Fred Hutch organization who review submissions of content to the Wiki.

Now that we’ve looked at accounts and organizations in GitHub, we can examine a few publicly available repositories.

Intro to Git and GitHub: The materials for this course are available in a repository,

with each class’ materials written in a Markdown (.md) file.

Markdown is a lightweight text-formatting language that allows creation of attractive documents. Markdown is especially popular for creating documents on GitHub, because the web interface automatically renders the formatting so they are easily readable.

Machkovech 2018 is the data analysis associated with a publication from a lab at Fred Hutch. This repository includes scripts, notebooks, data, and figures for the published manuscript.

ggplot2 is a very popular data visualization package for R statistical programming.

This repository includes all of the code needed to install and run ggplot2.

For more information on navigating and using GitHub, please see this resource page. If you would like additional information on managing your account, please go here.

Publishing a local repository

With this understanding of how GitHub operates, we can now publish some of our own work. We’ll use the repository we created in our previous class.

Open up GitHub Desktop,

making sure your first_repository is loaded.

Use the “Publish repository” button,

and uncheck the box next to “keep code private”.

This initializes a new repository in the remote GitHub servers,

and copies your repository’s code there.

Now you can view your repository on GitHub. There are two ways to get there:

- Under the “Repository” menu, select “View on GitHub”

- Go to

github.com/USERNAME/first_repository, whereUSERNAMEis your GitHub username

In the repository on GitHub, try and find the same features and information you’ve seen in your local repository on your own computer. In particular, the commit history should be identical to your local repository.

Pushing and pulling

Next, go back to your local repository. Make a change to one of your existing files and commit it.

After committing, the button in the top right of GitHub Desktop should now show the option to “Push origin”. Pushing in Git refers to sending all local changes to the remote repository. After clicking the button, go back to your web browser and view your remote repository. You’ll likely need to refresh the page to see the new changes.

It’s possible to create a remote repository on GitHub, and then connect it to an existing local repository. The button in GitHub Desktop is a shortcut that accomplishes multiple steps for you.

Our next step will be to perform the reverse action: make a change in the remote repository, and then add the changes to our local repository. The online GitHub interface allows you to edit and otherwise work with files. The web browser interface is great for making quick changes to files. Some things to know about this interface:

- You can edit a file by clicking the pencil icon in the top right of its window.

- After making changes in the edit window, click the “Preview” tab to see how it will render (primarily for Markdown files).

- You can edit only one file at a time; saving the change requires you to use the “Commit” button at the bottom of the page. This effectively saves, stages, and commits all in one step.

- Buttons to the top right of the file browser allow you to “Create a new file” and “Upload files”.

- To change the name or location of files (e.g., folder in which they are located), click on the pencil icon. The file name will appear in a modifiable text box near the top of the screen. You can add slashes in that path to create folders, or backspace at the beginning of the box to move the file to a higher level in the project structure. This only works for text files, however; other types of files will need to be organized in your local repository.

Once you’ve committed your change, go back to GitHub Desktop. The button in the top right will now read “Fetch origin”. Click this button so the software can compare the local and remote repositories. The button will change to read “Pull origin”, with the number in the bubble indicating how many commits will be added to your local repository. Click the button to synchronize the two repositories, and check to see that your change is now found in your local version.

Challenge-push

- Commit a change in your remote repository

- Without pulling the remote changes, commit a change in your local repository.

- What happens when you try to push, and why?

If you’ve decided you don’t want a repository published on GitHub any longer, you can delete it in your web browser by accessing the “Settings” tab near the top right of its GitHub page. Scroll to the bottom of the page to the section labeled “Danger Zone”, and follow the instructions to delete it. Note that you can’t undo a repository deletion on GitHub, although deleting the repository on GitHub does not affect your local copy.

Collaboration through forking

So far we’ve only worked with our own repositories. However, GitHub provides powerful features for interacting with other people’s repositories, too.

We’ll be using an example repository from the fredhutch.io GitHub organization called guacamole to learn about collaboration via GitHub. This repository represents information about making guacamole.

On each repository’s page, there is a tab under the title called “Issues”. Issues are a method of tracking tasks, document bugs, and otherwise plan for continued development of a project. Each issue may include:

- title and description, including information to replicate the problem in the case of a bug

- subsequent discussion about the issue

- labels indicating the type of issue

- information about who is assigned to the task, as well as its inclusion in milestones and/or projects (tools GitHub provides to set goals)

Challenge-issue

Create an issue in the

guacamolerepository suggesting how to improve the recipe.

Now that we have an idea of what needs to be done to improve this repository, let’s suggest some changes. This repository is owned by the fredhutch.io GitHub organization, so we don’t have permission to interact with it directly. Click the button called “Fork” in the top right corner of the repository’s GitHub page. Forking creates a copy of the original repository that belongs to you, so that you can edit the files contained within it.

In your guacamole fork,

edit ingredients.txt to include what you think needs to be included in this dish.

Forks allow repositories with early parts of their revision history to remain connected to each other,

so you’ll see a button called “Compare” above the file browser in the main repository page.

The page that appears shows the differences between your fork (“head repository”) and the original repository (“base repository”). If you are satisfied with your changes, click the button to “Create a pull request”. A pull request, or PR, notifies the original repository’s owner that you have made changes that you’d like to be included in the original repository. The page that appears automatically enters the specific comparison from the “Comparing changes” page. There are also text boxes that allow you to enter a title and description. These are your opportunity to explain what files are being changed and why. You have the ability to link issues, tag people, and otherwise communicate your intentions. When you click the button to “Create pull request”, your submission will be viewable under the “Pull requests” tab (next to Issues under the repository’s name).

After submitting a pull request, the owner of the repository will be notified, and they’ll be able to review the suggested changes. The pull request page in their repository includes space to share additional comments. When the original repository’s owner is satisfied with the changes, they will merge the changes, after which you can delete your branch from your own fork. Alternatively, they may not accept your pull request, and will instead close it without merging. In that case, you can decide how to proceed: if you like the work you’ve done, you can always continue working on your own fork!

Challenge-pr

Create a pull request to ask that changes in your

guacamolerepository be added to the fredhutch.io version. Your instructor will select a pull request to demonstrate the process of merging (accepting changes).

You may have noticed earlier that there was an option to select the branch from your fork to compare. This is because the pull request only includes a single fork from each repositories. Any subsequent changes you make to your branch associated with the pull request will be reflected in the pull request. This means you can make additional changes in response to your collaborators. It also means that if you delete your branch, your pull request will be impossible to merge.

In this section,

we’ve worked through the process of submitting a pull request to a collaborative project using the “fork and pull” development model.

Alternatively, some (generally small) projects use a “shared repository” model,

in which all contributors are added to the same repository,

and individuals work on separate branches.

In both cases,

pull requests are used to show differences among branches and share discussion about the changes.

For more information on these two models,

see this page.

If you are in doubt about how to contribute,

check the repository to which you’d like to submit a pull request.

Many projects share guidelines about how to contribute to their project in their README or a separate file named something like CONTRIBUTING.

When in doubt,

create a fork: it doesn’t require additional sharing of permission on the part of the original repository owner.

Be aware, though,

that not everyone interacts with Git and GitHub in the same way,

so sometimes it takes a few messages back-and-forth to get on the same page about what will work for you both.

Challenge-patch

Go to the repository for the Fred Hutch Biomedical Data Science Wiki and click on the page for

about.md. You do not have permission to contribute directly to this repository, but there is still a pencil icon at the top right of the file content viewer. Click on the pencil and read the information box at the top of the page. What would you do, and what would happen, if you wanted to suggest changes to this file? This exercise assumes you are not currently a part of the Fred Hutch GitHub organization. If you are already a member of this organization, choose a different repository to which you do not currently have access (like the repository for this class).

Resolving conflicts

The pull requests we’ve encountered so far have been straightforward in the sense that the changes were easily accomodated in the original repository. Sometimes pull requests involve changes that overlap with a previously merged pull request, and Git cannot differentiate which changes are preferential, since they both occurred since the last shared commit in history. In these cases, Git reports that conflicts have occurred by a box at the bottom of the pull request page stating “This branch has conflicts that must be resolved”. By clicking on the “Resolve conflicts” button, an interface appears that highlights the conflict, including the following:

<<<<<<<followed by the branch name and the suggested change from the PR=======, which separates the two conflicting changes>>>>>>>followed by the branch name and the original repository’s content

Resolving the conflict requires deciding how to reconcile the changes,

as well as removing the conflict notation (symbols < = >).

After resolving the conflict,

the “Mark as resolved” button will become clickable.

The interface will prompt to “Commit merge”.

This commits the conflict resolution,

and will afterwards return to the pull request page.

The final step will be to normally merge and close the pull request.

Your instructor will demonstrate how this works using an additional pull request for guacamole, but for another set of instructions please go here.

Cloning vs downloading

Now that you have an idea of how remote and local repositories can be related to each other, it’s worth noting how you can access someone else’s code that is currently available on GitHub. We’ll use an example code repository as an example.

On every GitHub repository’s online webpage, there is a green button near the upper righthand side of the screen that says “Code”. This button allows you to obtain a copy of that repository’s contents on your local computer. If you click the button, there are two options from which to choose: “Open with GitHub Desktop” and “Download ZIP”.

The first option will copy the contents of the repository to your local computer and open it using GitHub Desktop. This option retains the entire history of the repository as tracked by Git.

The second option downloads a zipped copy of the default branch of the repository to your computer. If you select that option for [], you’ll end up with a file called “example_analysis_repo-main.zip” (or a folder called “example_analysis_repo-main”) in the default location for downloads on your own computer. This folder contains all of the files in the repository, but only a snapshot of the most recent commit. This file does not contain the version history as tracked via Git. You can confirm this by attempting to access this folder via GitHub Desktop: it won’t be recognized as a Git repository.

The main lesson here is to use the method of access that makes sense for your specific needs: if you’re going to be working with past versions of files, or continuing to track changes (especially if you’d like to contribute back to the project), you should clone the repository. If you’re only interested in looking at the existing files for reference, downloading should be sufficient.

Wrapping up

Today, we explored the use of GitHub to publish our own code/data, as well as how to contribute to someone else’s repository using GitHub. The GitHub.com help documentation includes additional examples and illustrations for the tasks we covered today (and more!).

Our next (and final) class is also optional. It will review the materials from the first two classes as implemented on the command line, and also highlight a few things that the command line interface can accomplish that aren’t possible with the tools we’ve used so far.